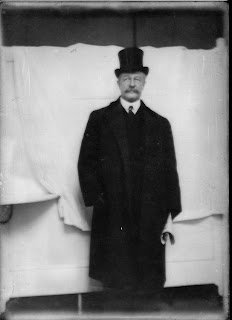

This 5x7 glass plate negative made in the nineteenth century was made into a print by scanning using a flatbed scanner. The mix of materials and techniques in photography bridges technology and melds 100 year old images with modern techniques. While the image, the art, remains, the techniques are in a constant state of change.

When lovers of great literature gather they rarely debate the make of typewriter used by Hemingway, or the paper on which he typed his first draft of A Farewell to Arms. Yet photographers tend to spend an inordinate amount of time discussing equipment and technique. Naturally, lively talks about inspiration and vision take place, but only critics and outsiders seem to disdain the important matters of craft. Those who practice photography know instinctively that there is no wall between the art and craft of photography.

Photography is a field in which this dialectic is affirmatively resolved, where discipline of craft equals freedom of expression. It’s as if a painter could create a painting without knowing how to mix paint. It might work, but some subtlety of expression would be lost.

Even the briefest study of photography leads to the conclusion that the greater ability to express, and the expanded modes of expression are intimately tied to the evolution of the ways and means of taking and making pictures. While the subject of the image is often a child of its age, an expression of the attitudes and social mores of its times, the mechanics of camera, processing and printing is often as much a part of the image as the idea communicated in the image itself. Though new ways of seeing are at the core of the evolution of photographic art, the defining principles of that vision are greatly determined by the equipment and processes used to manifest that vision.

Arguments have been made that portraits made in the first thirty years of photography surpass in beauty, charm and revelation of the human spirit those made today. Those images were more startling to their contemporary viewers than most photographs are to us today, if only because the medium was nowhere near as prevalent as it is now. Yet the revelation of character in today's fine portraiture, with all the layers of meaning we bring to the image, could only be achieved with today's equipment used by today's photographers.

Just as with early photographs, admittedly viewed through the filter of the ravages of time, the images created today are subject to the matrix of vision that is bounded by our ability to manifest that vision. That is why with each progression in technology there is so much more visual expression to explore.

The vigor with which photography grabbed the human imagination can be traced to its serving both masters so well. Essential to its understanding is that it addresses most directly the very human need to communicate through images, and plays upon the human ability to empathize with abstract forms. Thus, the mechanical serves the artistic, which in turn creates communication on virtually every level of visual perception.

The linkage between the art and craft has its roots in those people who pioneered modern photography. Many of the early explorers were artists seeking new and more efficient ways to create images from nature. Many were men and women who were grounded in the scientific method of discovery, yet who were also practicing artists, or associated with circles concerned as much with aesthetics as they were with experimentation.

Photography sprang from a time when the lines between science, art and craft were no so clearly drawn, and when curiosity went beyond prepackaged solutions to meaningless problems.